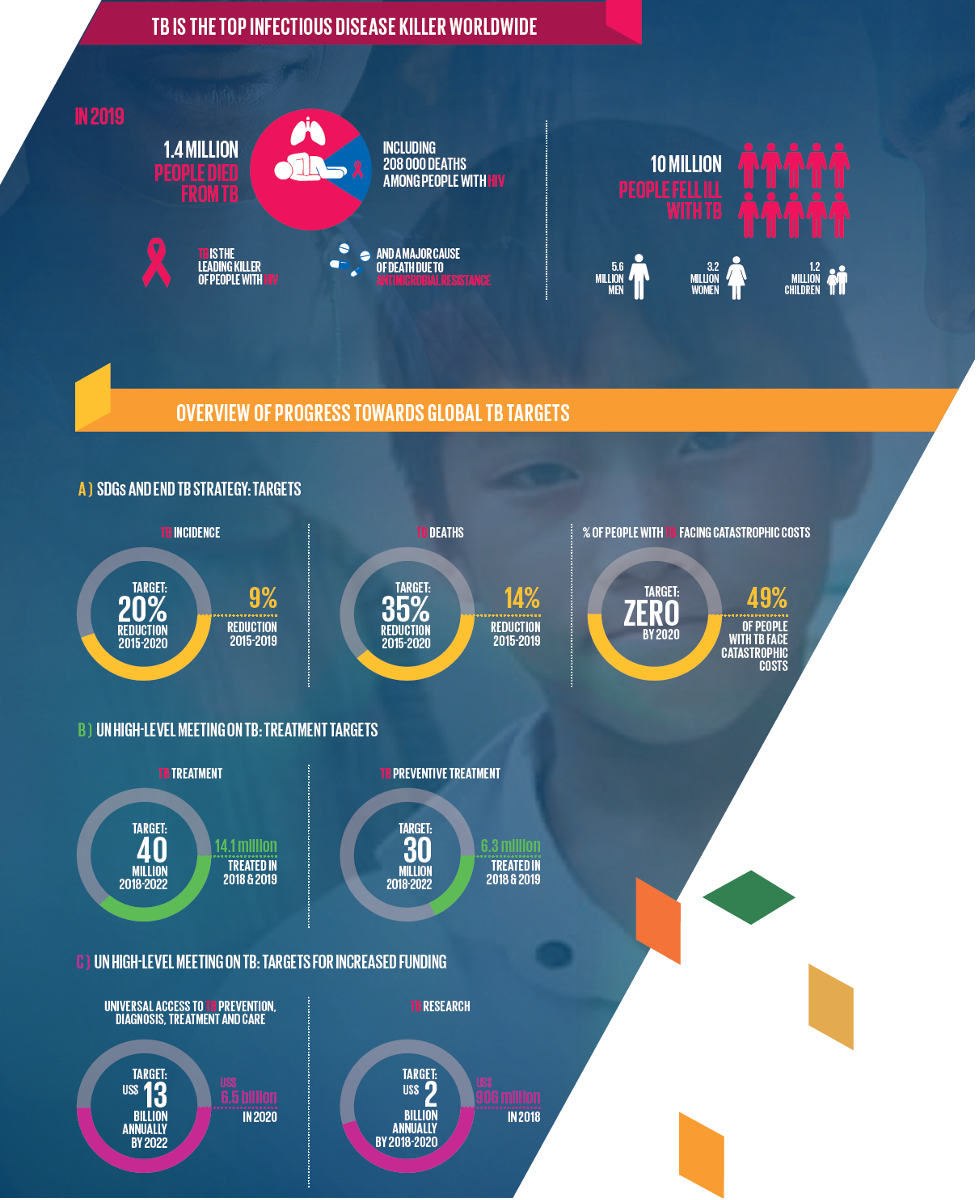

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the top 10 causes of death worldwide surpassing HIV/AIDS. Globally, an estimated 10.0 million (range, 8.9–11.0 million) 5 people fell ill with TB in 2019, a number that has been declining very slowly in recent years. There were an estimated 1.2 million (range, 1.1–1.3 million) TB deaths among HIV-negative people in 2019 (a reduction from 1.7 million in 2000), and an additional 208,000 deaths (range, 177,000–242,000) among HIV-positive people (a reduction from 678,000 in 2000) (Global Tuberculosis Report 2020).

The severity of national TB epidemiology varies significantly among countries. The unfortunate side of the world with their iron mines and sweatshops has fifty times the incidence of TB as in high-income countries. Geographically, most people who developed TB in 2019 were in the WHO regions of South-East Asia (44%), Africa (25%) and the Western Pacific (18%), with smaller percentages in the Eastern Mediterranean (8.2%), the Americas (2.9%) and Europe (2.5%). Eight countries accounted for two- thirds of the global total: India (26%), Indonesia (8.5%), China (8.4%), the Philippines (6.0%), Pakistan (5.7%), Nigeria (4.4%), Bangladesh (3.6%) and South Africa (3.6%) (Global Tuberculosis Report 2020). The TB incidence rate at the national level varies from less than 5 to more than 500 new and relapse cases per 100,000 population per year. In 2019, 54 countries had a low incidence of TB (<10 cases per 100 000 population per year), mostly in the WHO Region of the Americas and European Region, plus a few countries in the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific regions. These countries are well placed to target TB elimination (Global Tuberculosis Report 2020).

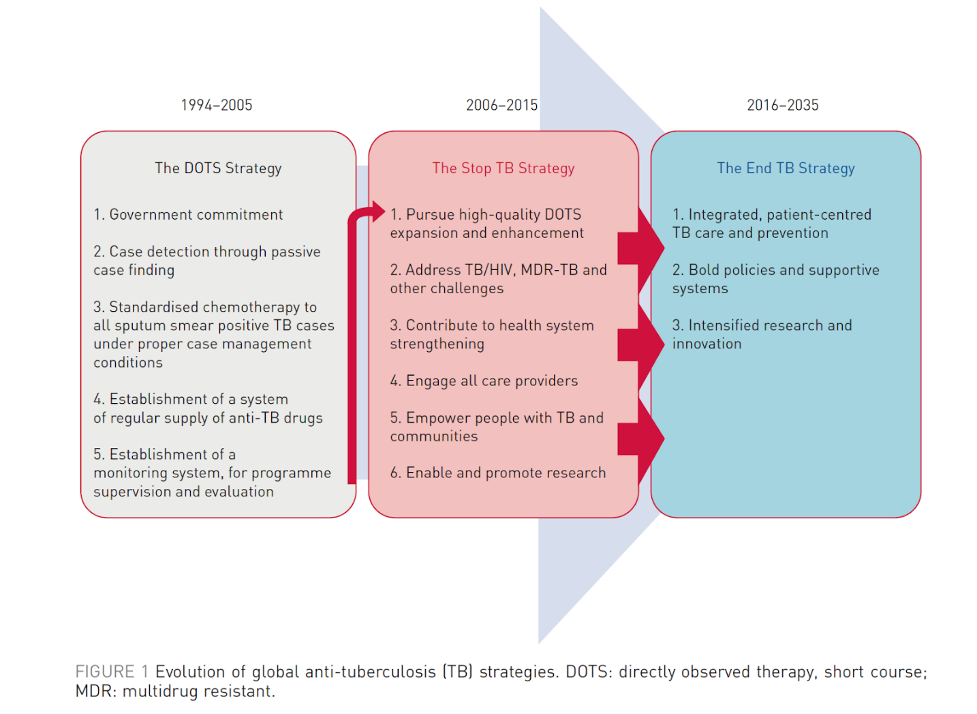

Until recently, the fight against TB was designed to pursue control of the disease, e.g., ensuring that infectious cases are rapidly diagnosed and effectively treated, thus breaking the chain of transmission (Tuberculosis elimination: where are we now? | European Respiratory Society).

Figure 1: Evolution of global anti-TB strategies

Severe critical challenges can be identified that hamper effective TB control. Persistently high TB mortality can be reduced by earlier diagnosis and treatment. For as many as 3 million estimated TB cases we have no notification, 3 million victims of TB suffering without receiving professional care, and this raises serious concern about optimal clinical and public health management. This is mainly attributed to incomplete compliance of private providers in some countries, while economic barriers to primary care access might determine underdiagnosed TB in low-income countries.

COVID-19 has affected the TB control effort in a devastating way that needs to be addressed and its effect may last for years to come.

Over the past 14 months, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted health services globally and has negatively impacted on gains being made in global TB control efforts to achieve End TB targets.

In this blog post I will try to summarize the End TB Strategy, and reflect on whether we can really meet the global vision for TB elimination by 2035? I will use my own country, Oman, as a model to reflect on an individual country's efforts to meet the mandates for the End TB Strategy.

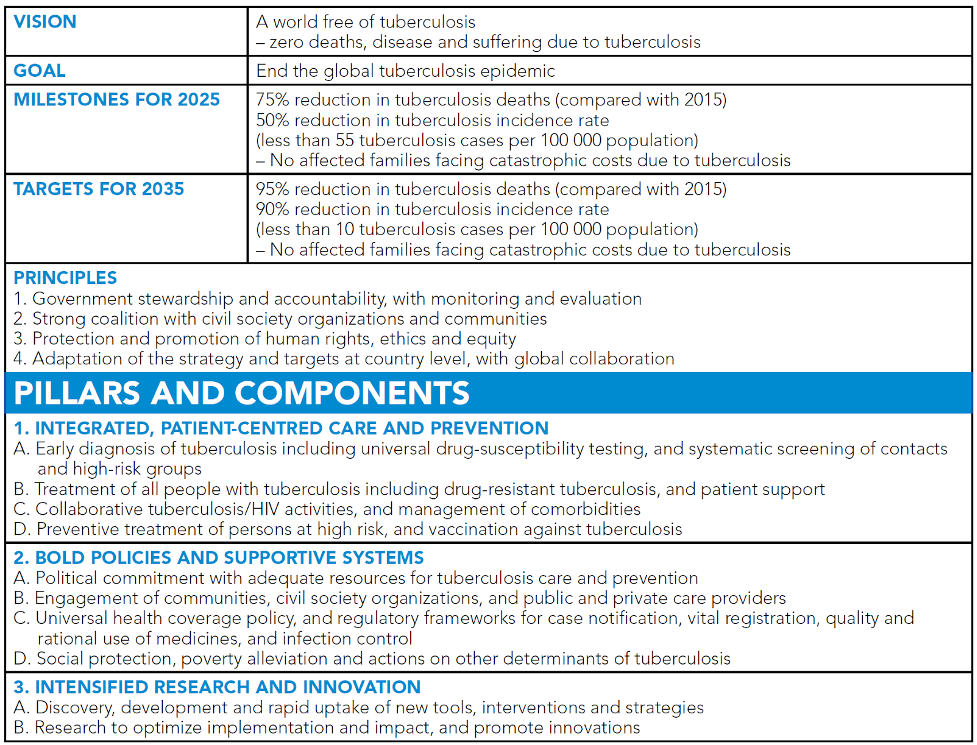

The WHO End TB Strategy

The World Health Organization (WHO) End TB Strategy aims to end the global TB epidemic by 2035, reducing global TB incidence and mortality rates by 90% and 95%, respectively, in 2035 when compared to 2015. In September 2018, the goal of ending TB was elevated to the highest level at the first-ever United Nations (UN) high-level meeting on TB in New York which brought together heads of states and governments who made bold commitments to accelerate the TB response. The WHO End TB Strategy was developed in parallel with the Sustainable Development Goals, and interventions should be anchored in these.

Figure 2: post-2015 global End TB Strategy framework

Figure 2: post-2015 global End TB Strategy framework

Oman as a pathfinder to TB elimination

Oman is a low TB incidence country; Oman’s TB programme is committed to provide quality surveillance data and free quality clinical management. Universal access and social protection mechanisms are in place.

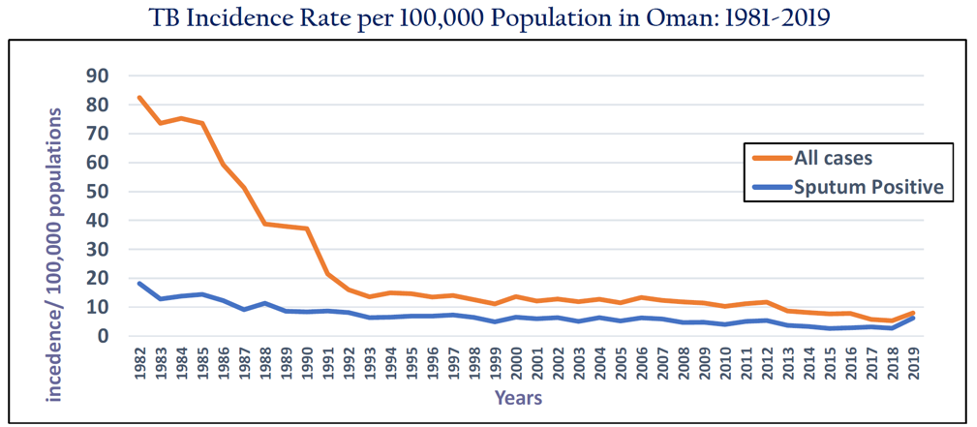

Incidence rate of TB in Oman dramatically reduced in the last 30 years from 90.98 per 100,000 population in 1981 to 5.3 in 2018 (all forms) and 19.61 to 2.7 per 100,000 (for sputum positive pulmonary TB) in nationals. with an annual incidence rate of less than 5.3 cases (all cases) per 100 000 population in 2018.

Figure 3. The trend in tuberculosis incidence in Oman—1981–2019

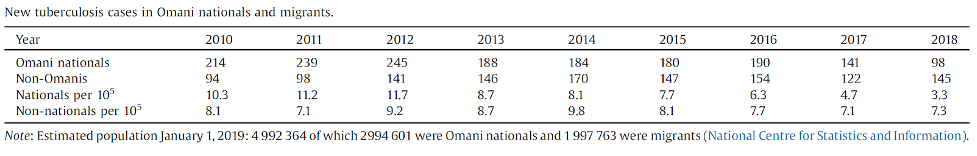

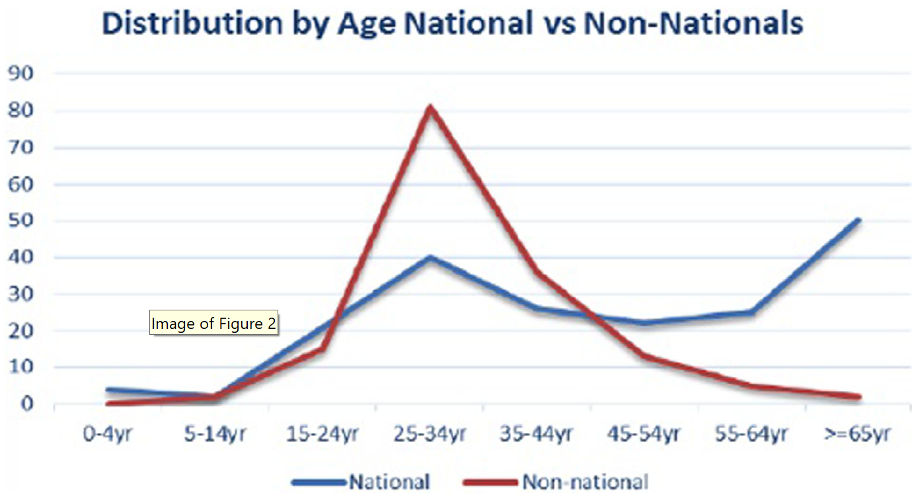

Forty-one percent of the population in Oman are migrants from high-incidence countries, countries with more than 100 cases per year per 100,000 population, accounting for 60% of the annual TB cases (Table 1)

Table 1. Age-specific annual tuberculosis incidence in Omani nationals and non-Omanis.

Table 1. Age-specific annual tuberculosis incidence in Omani nationals and non-Omanis.

Figure 4. Distribution of TB case by age and Nationals vs non-Nationals

Figure 4. Distribution of TB case by age and Nationals vs non-Nationals

The proportion of active pulmonary TB cases among Omani nationals and non-nationals has been changing over the years, with a decreasing number in Omanis and an increasing number diagnosed in non-Omanis.

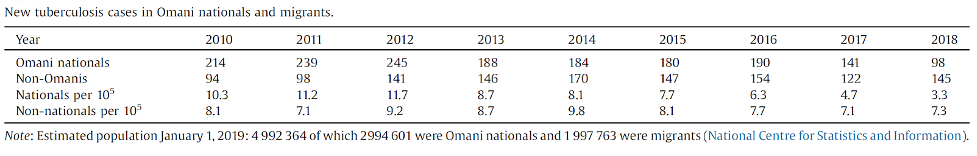

Table 2. Age-specific annual tuberculosis incidence in Omani nationals and non-Omanis.

Table 2. Age-specific annual tuberculosis incidence in Omani nationals and non-Omanis.

In 2019, the incidence of notified sputum smear-positive cases was 38.1 per million population and that of all forms was 77.9 per million; for Oman-born individuals, the incidence was 28.4 and 78.2 per million, respectively, and among foreign-born people, 49.8 and 77.5, respectively. Management of LTBI is considered core to the pursuit of TB elimination and contacts of any TB case are systematically screened using interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs) or the Mantoux test. Until 2017, the national policy for TB control was based on the screening of migrants on arrival for active pulmonary TB with a chest X-ray. Since 2017, investigations for active pulmonary TB have included sputum microscopy, culture and PCR if there is a clinical or radiological suspicion of TB. Pre-arrival screening is also conducted in Gulf Collaboration Council certified centres in the country of origin of migrants for around 90% of the migrants (https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/51/1/1702027.long).

Out of LTBI treatment standards for contacts included isoniazid monotherapy, and since 2017, the MoH Oman has introduced the 12-dose combination regimen of rifapentine and isoniazid in order to improve adherence and the treatment completion rate. In 2017, the national TB programme introduced the LTBI treatment outcome registry at the national level, using electronic forms.

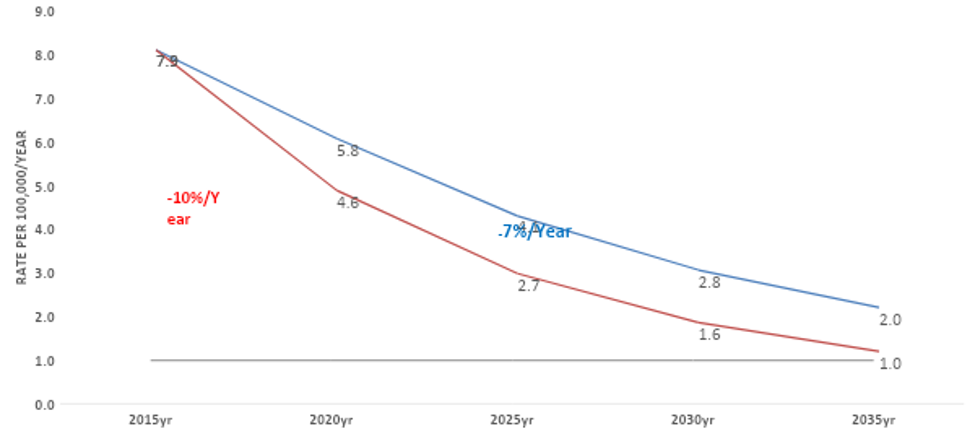

Reducing the current incidence of 59 cases per million population to less than 1 per million by 2035 will pose significant challenges.

The Ministry of Health (MoH) estimated that Oman has to reduce the incidence by around 10% per year to reach the goal of a 90% reduction in the incidence rate by 2035.

Figure 5. Projected Reduction Rate to reach 90% reduction in TB incidence (<1/100,000), Comparison of reducing TB by 10 versus 7% per year

Figure 5. Projected Reduction Rate to reach 90% reduction in TB incidence (<1/100,000), Comparison of reducing TB by 10 versus 7% per year

Oman fulfills the first three goals of the pillars of the End TB Strategy and partly the fourth, “Preventive treatment of persons at high risk, and vaccination against tuberculosis”, by including universal bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) immunization at birth and preventive treatment of contacts of known active TB cases. The current strategy does not include the screening of migrants from highly endemic countries for LTBI.

Points 5–8 of the TB Elimination Framework are partly fulfilled in Oman, in that there are political commitment and universal government-funded healthcare coverage and regulatory frameworks for case notification, vital registration, quality and rational use of medicines, and infection control.

To move forward towards TB elimination, the Oman MoH worked to establish a TB elimination strategy. Once the strategy was drafted, MoH Oman organized an international meeting on TB elimination in low incidence countries on 5-7 September 2019, supported by the WHO and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. A case-study was built, and a writing team of global TB experts was invited to summarize the available evidence for the different areas with a non-systematic approach and to discuss this evidence based on the Oman-specific data. Several rounds of discussion were organized to reach consensus on the final document. I summarize below the main recommendations (Tools to implement the World Health Organization End TB Strategy).

Specific interventions for national TB control and elimination programmes in the End TB era

Multisectoral collaboration and political commitment

TB is a disease of poverty and deprivation which can only be controlled by involving multiple stakeholders and addressing the need of marginalized groups with a high incidence. Political commitment is key to addressing the complex interaction between socioeconomic problems and healthcare provision. One example is the Zero TB Initiative, which creates support for local stakeholders helping to mobilize financial and technical resources. Examples are the mobile units in rural areas of South Africa providing treatment, and mobile chest X-ray units in Karachi, Pakistan (Zero TB Initiative).

The government of Oman will support policies which inform migrants in their own language of their right to seek medical care, identify the signs and symptoms of TB, and the right to free treatment in Oman without the risk of being repatriated in the case of active pulmonary TB.

The End TB Strategy was reiterated in the Moscow Declaration adopted at the First WHO Global Ministerial Conference on ending TB in 2017 where ministers of health including the minister for Oman, declared “We reaffirm our commitment to end the TB epidemic by 2030”. The Moscow Declaration called for the development of a multisectoral accountability framework, which was reiterated in the UN High Level Meeting Political Declaration by heads of state.

Managing LTBI in migrants

Oman is characterized by a local population with a low incidence of TB and a large population of migrants with a higher incidence of TB. Managing LTBI in this population is a clear priority. A study from the Netherlands found that the most important predictor for developing active TB was known exposure, but being foreign-born was an independent risk factor , and 72% of new TB cases were foreign-born.

Diagnosis of LTBI

Mandatory health examinations of migrants in Oman takes place at pre-entry, on arrival and then every 2–4 years as part of visa renewal. A chest X-ray is included in these medical examinations which may potentially identify cases of active pulmonary TB.

A pilot study from Oman found that 21% of migrants from Asia and 31% from Africa were IGRA-positive.

Management of LTBI in migrants to Oman

A pragmatic approach to reduce TB incidence could be to select the migrants with a strongly positive IGRA of >4 IU/ml and offer preventive therapy of three months of combined rifampicin or rifapentine and isoniazid. In 2018, 943 377 migrants were examined in the medical migrant examination centres in Oman, and 33% (311 314) of them were new arrivals. The study of IGRA reactivity in migrants showed that 22.4% had a positive IGRA, i.e., 69 734 out of the 311 314 new arrivals.

Extending the service by developing public–private partnerships

In 2018, 3 million of the estimated 10 million people with TB worldwide were ‘missed’ by national TB programmes (WHO TB report 2019). Two thirds were thought to access TB treatment of questionable quality from public and private providers who were not engaged by the national TB programmes. The quality of care provided in these settings is often not known or substandard (WHO TB report 2019). To close these gaps, the WHO and partners have launched a new roadmap to scale up the engagement of public and private healthcare providers.

Also, in Oman, the future challenges of the TB control programme need resources provided by the private health sector, both in diagnostics and the management of LTBI. The government is committed to providing treatment for both LTBI and active TB, to both Omani nationals and migrants. This will be done either in public or private facilities.

Involvement of the private sector in the diagnosis and management of LTBI requires a quality control programme for the diagnostic tests used and regular reporting of treatment outcomes, including compliance. The government needs to develop models for cost covering of services – diagnostic and clinical – provided in the private sector within the framework of universal health coverage (UHC), as has already been done successfully in countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, India and Indonesia. UHC was addressed at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) on September 23, 2019 (UN HLM 2019). The Oman Minister of Health, at a side event held on multisectoral action to end TB hosted by WHO and the Russian Federation at the UNGA, stressed the need for greater commitment in reaching vulnerable groups such as migrants. He called for greater partnership across all sectors, including the private sector, to reach this goal.

Figure 6: A tweet from Dr Tereza Kasaeva, Director - World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Programme

Figure 6: A tweet from Dr Tereza Kasaeva, Director - World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Programme

Developing molecular characterization by whole genome sequencing (WGS) to uncover transmission routes and define clusters and detect genotype resistance

A single study from Oman used spoligotyping to explore the genetic population structure and clustering of Mtb isolates among nationals and immigrants (Al-Maniri 2010). The study found a predominance of the strain families commonly found on the Indian sub-continent. A high proportion of immigrant strains were in the same clusters as Omani strains.

However, spoligotyping has a very low discriminatory power compared to WGS.

Genotyping Mtb strains from TB patients over time provides detailed information on the Mtb transmission dynamics, and it is possible to determine transmission among and between nationalities. This information can be used to optimize the public health management of TB, e.g. by directing the TB control efforts to specific risk-groups. In Oman specifically, WGS will be useful to determine the amount of transmission between migrant workers and Omanis and to identify high-risk groups and hotspots for active TB transmission within the country.

In addition, systematic use of WGS on all Mtb isolates will allow the emergence of drug resistance to be monitored and, if implemented from early liquid culture, could allow the cost of phenotypic drug sensitivity tests on strains that are fully wild-type for first-line drugs to be reduced. This strategy will be fully compliant with pillar 1: early diagnosis of TB including universal drug-susceptibility testing, and systematic screening of contacts and high-risk groups.

Patient-centred care including treatment support

The key challenge with programmatic LTBI screening is compliance with preventive treatment. A recent review of LTBI treatment in

migrants found an overall poor level of compliance (Greenaway 2018), and one possibility is to extend the community-based treatment support to cover preventive treatment of LTBI. During two years of community-based care delivery in Muscat Governorate, 18 out of 27 Omani pulmonary TB patients were included in 2017 and all Omani nationals with pulmonary TB (n = 16) in 2018, except two new cases, were on community-based care delivery. Even though community preventive treatment support is not presently offered to people with LTBI, some form of support to ensure adherence that is either family or community based would be desirable. To increase compliance, the 3-month course with a rifapentine orrifampicin/isoniazid combination is much preferred.

TB in high-risk groups

Healthcare workers

The United States recently (2019) revised its recommendations for the surveillance of TB in healthcare workers, because the risk was determined to be very low. The new recommendations include baseline (pre-placement) TB screening with an individual risk assessment and symptom evaluation for all personnel, and testing with an IGRA or tuberculin skin test for personnel with known exposure to TB.

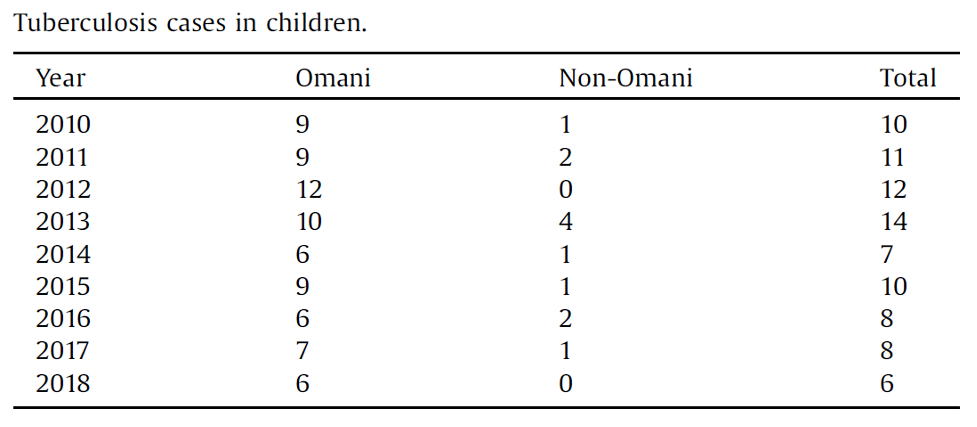

TB in children

86 TB cases that have been registered in children in Oman from 2010 until 2018 are shown in the table below.

Table 3: TB cases in children in Oman

Table 3: TB cases in children in Oman

Children pose unique challenges to TB control programmes, as infection in this age group is considered a sentinel event indicating recent transmission. The importance and priority of children as a special high-risk group was highlighted in the WHO End TB Strategy.The main interventions to prevent new cases in children are vaccination with the BCG vaccine, contact tracing and screening for active TB, and treatment of LTBI. The WHO has strongly recommended treatment for LTBI in children under 5 years of age who are household contacts of pulmonary TB cases.

Screening algorithms and cost-effectiveness

Current LTBI screening is limited by the relatively low positive predictive value of available tests. Although the positive predictive value appears better for some IGRA tests compared with the tuberculin skin test, defining reactivation risk varies significantly by population group. The selection of the population group determines the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the approach. Thus, screening those at highest risk of reactivation, such as persons with immunosuppression, is most cost-effective, and this has led to the recommendation to focus on these high-risk groups for LTBI control (WHO, 2017; ECDC 2018). In the context of TB elimination and the large estimated numbers of persons with LTBI, strategies need to include further groups based on stratification by epidemiological risk factors (country of origin, time since arrival), demographic factors (age groups), co-morbidities or social risk factors.

Modelling

Mathematical modelling provides important tools for the assessment of potential strategies and allows for comparison of a wide range of possible approaches with relatively minimal resource implications. In the specific context of Oman, mathematical modelling approaches could be used to consider the optimal screening algorithms for latent and active TB in migrants and nationals, and to evaluate the efficiency of different strategies.

Research

There is a need for operational research aimed at optimizing the cost-effectiveness of the different interventions, identifying high risk groups in the community, follow-up of persons with LTBI without treatment, and stratification of the risk of developing active TB based on the strength of the IGRA level or tuberculin skin test reactivity.

The existing mandatory health investigation including a chest X-ray every 2–4 years will ensure that follow-up is done if the migrant stays in Oman. This will allow studies on the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of active TB screening in combination with LTBI or LTBI only.

Models for public–private partnerships to enlarge affordable coverage for all, need to be developed, tried and validated.

Following the 2019 international workshop in Muscat, MoH Oman revisited the National Strategic Plan For TB Elimination and fine tuned it. The plan will officially be launched on 24th March 2021 by the Minister of Health of Oman, the main pillars of the national strategic plan for TB elimination are the following:

Detect

- Mtb/RIF Resistant Xpert have been introduced as the initial test for presumptive TB cases along with sputum microscopy, culture and susceptibility testing

- Detection of drug resistant have been upgraded by using molecular testing such GeneXpert, line probe assay

- Preparing for the introduction of WGS

- Drafted Public Private Mix action plan and proposing standard models to improve active case finding among Non-Nationals at the private institutes

Treat

- Government commitment to ensure free treatment for both Nationals and Non-Nationals

- Integrated patient-centred approach and introduction of Community DOT

- Treatment of all contacts of active TB cases and high risk groups

- Introduction of shorter regimen for latent TB treatment (Refapentine & INH) as the treatment of choice for LTBI for all contacts of TB patients

- Management of multidrug resistant TB under expert ID/respirologist

- Update the infection prevention and control guidelines at hospital and primary healthcare including recommendation for triage, environmental and administrative controls, and airborne infections isolation rooms

Prevent

- Screening migrants arriving from endemic countries for TB

- Cost effectiveness study was conducted to assess the introduction of screening of migrants for LTBI using IGRA

- National policy for screening and treatment of healthcare workers for blood borne viruses and active and latent TB

- Integrate TB/HIV/STI services

- Risk communication to improve awareness among community members

- Health promotion activities to cover both nationals and non-nationals, improve acceptance of LTBI screening and treatment among the nationals and healthcare workers

Monitoring and evaluation

- Establishment of national objectives and key results for the elimination of TB according to the national strategic plan for TB elimination

- Standardize and update monitoring and evaluation system

- Integrate monitoring and evaluation system into the national electronic surveillance system

- Development of key performance indicators at governorates and central level

Research

- Intensified research is a major component of End TB Strategy to understand the transmission dynamic and find an innovative method to reach TB elimination targets

- The Oman Central Public Health Laboratory has received a grant from the Oman Research Council on “Understanding TB transmission and epidemiology using molecular and geo-spatial methods”, and this will be incorporated into the routine surveillance in the future.

- Cost-effectiveness of screening and treating migrants for LTBI

The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on TB programs

The COVID-19 pandemic has direct and indirect negative impacts on health services overall, including national TB programs affecting TB health services, interrupting and slowing down treatment and prevention efforts.

COVID-19 challenges add further to longstanding challenges for tackling MDR-TB such as availability of budgets, rollout of TB diagnostics and TB drugs. In addition, COVID-19 dramatically impacted the TB/HIV health services, especially in low-income countries such as sub-Saharan Africa. We need urgent interventions to mitigate the growing burden of these colliding epidemics which bear significantly high proportions of TB and HIV cases reported worldwide in comparison to high-income countries. The pandemic has added an additional burden to already overstretched health systems in the low and middle-income countries. The COVID-19 pandemic threat to derailing health services for forcibly displaced people and migrant populations, populations who face specific vulnerabilities placing them at increased risk of developing TB if they have LTBI, or not being diagnosed as having active TB. Implementation of the latest WHO guidelines for MDR-TB, in light of COVID-19 disruption of TB services will be difficult and it is anticipated the numbers of MDR-TB cases will rise in this year and 2022 and will affect MDR-TB treatment outcomes further.

There is a need for urgent interventions to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on TB services. Some of these interventions include strengthening and expanding the existing infrastructure for TB care to tackle both COVID-19 and TB in migrants and refugees in an integrated and synergistic manner. We also need to closely align and optimize COVID-19 and MDR-TB algorithms and improve clinical capacity to offer rapid diagnosis, quality treatment and follow-up and ensuring the availability of quality, regular supply of cost-free TB drugs (for both DS-TB and MDR-TB) through improved procurement and distribution of TB drugs.

So Is It Still Realistic To Reach TB Elimination By 2035?

On 26 September 2018, the United Nations General Assembly decided to hold the first-ever high-level meeting (UNGA-HLM-2018) on the fight against tuberculosis, under the theme “United to end tuberculosis: an urgent global response to a global epidemic”. The meeting aimed at accelerating efforts in ending TB and reaching all affected people with prevention and care. The global leaders signed the UNGA-HLM-2018 declaration which committed to mobilize 15 billion USD per annum for TB, 13 billion USD for TB care and 2 billion USD per annum for TB research and development.

The United Nations conducted a follow-up meeting on 23rd September 2020 during the 75thUN General Assembly (UNGA-2020) and a report on “Progress towards achieving global tuberculosis targets and implementation of the UN Political Declaration on Tuberculosis” was issued.

Figure 7: Overview progress towards global TB targets

Figure 7: Overview progress towards global TB targets

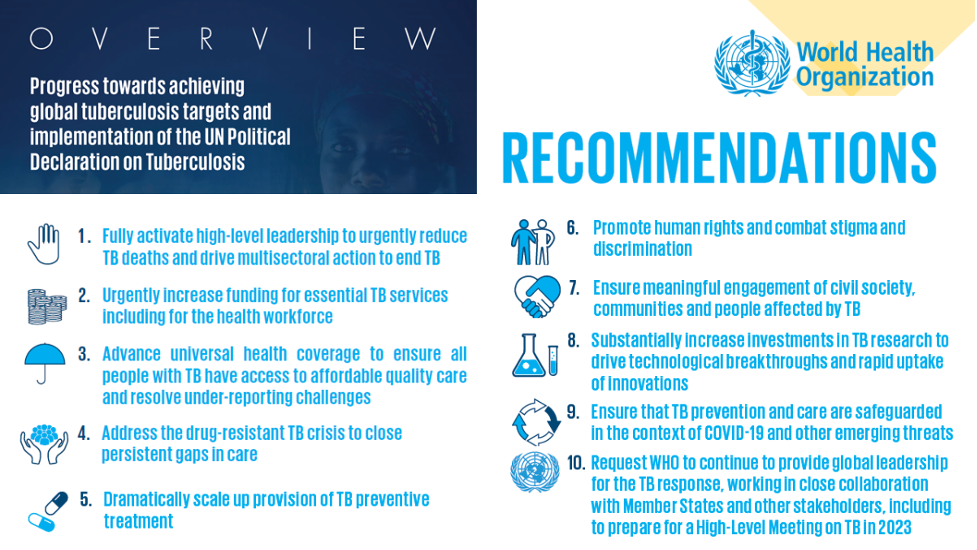

Overall, the report shows that high-level commitments and targets have galvanized global and national progress towards ending TB, but that urgent and more ambitious investments and actions are required, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. 10 priority recommendations are outlined to put the world on track to reach agreed targets by 2022 and beyond, and reduce the enormous human and societal toll caused by TB.

Figure 8: the 10 priority recommendations for countries to put the world on track to reach agreed-on targets by 2022 and beyond

Figure 8: the 10 priority recommendations for countries to put the world on track to reach agreed-on targets by 2022 and beyond

Reflecting on the current TB control strategies in light of the UN targets set in the political declaration at the UNGA-HLM-18, progress in achieving TB control targets has been very slow. In view of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on TB services, it is anticipated that the End TB Strategy target of controlling TB by 2035 will not be met. The WHO 2020 TB Report revealed a 50% drop in the number of people with TB detected and could result in up to 400 000 additional TB deaths in a year.

The theme of this year’s World TB Day 24th March 2021, ‘The Clock is Ticking’ conveys the urgency that the world is running out of time to deliver the commitments to end TB made by global leaders at the NGA-HLM-2018. This ticking clock is particularly appropriate and critical considering the devastating COVID-19 pandemic.

On World TB Day 2021, every politician, community leader and funding agency must get the message that it is time to reduce inequities as we work towards a TB-free world. While there is a continued need to develop new prevention and treatment tools for TB, obtaining the resources required for the implementation of current TB diagnostic and management tools could significantly advance TB control efforts. World leaders need to urgently address and reverse the socioeconomic and health services impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. As the accelerating roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines, especially with the Covax Vaccine Roll-out, starts to influence slowing down the COVID-19 outbreak, every effort must be made to ensure that health services and prevention programs for TB are not rolled back further.

In summary

Although epidemiological plausibility for TB elimination exists, fulfilling the WHO End TB Strategy and the WHO TB Elimination Framework requires a comprehensive package of strategies, and a great effort is needed by national public health authorities to implement the core activities of the End TB Strategy in different settings in all countries and regions. The higher political commitment should be considered one of the highest priorities. At the same time new prevention, diagnostic and treatment tools are also necessary in order to increase the speed of the present TB incidence decline. Challenges of achieving TB elimination in a low endemic country like Oman with a high number of migrants from high TB endemic countries, clearly shows that screening for LTBI and the treatment of either all cases with LTBI or high-risk cases, is a key intervention to reduce new cases. In more high-endemic settings, the identification of high-risk groups and screening these for LTBI, followed by preventive treatment, is an initial strategy. The development of public–private partnerships is needed to handle the burden of screening and treating migrants for LTBI. Innovative plans are needed to maintain all TB services including diagnostics, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and investments in the development of low-cost rapid diagnostic tests for both COVID-19 and TB, and aligning services are urgently needed.

With high-level political commitment and with an actionable National Strategic Plan For TB Elimination, Oman could be among the first countries to achieve TB elimination and serve as a pathfinder for the WHO EMRO region and the world.

The International Journal of Infectious Diseases, the official journal of the International Society of Infectious Diseases will publish a special issue on the occasion of World TB Day, so keep watching for the new articles that will cover the current global status of TB and critical thinking on how to move forward to meeting the target of reaching TB elimination by 2035.

Written by ISID Emerging Leader Dr. Seif Al-Abri