GUIDE TO INFECTION CONTROL IN THE HEALTHCARE SETTING

INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL IN THE RADIOLOGY DEPARTMENT/SERVICE

Author: FATMA AMER, MBBCh, MSc, PhD

Chapter Editor: VICTOR ROSENTHAL, MD

Print PDF

DEFINITION

Over the last three decades, the role of medical imaging has extended from diagnosis to include more interventions. So, there is a need for standardized infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines, particularly in interventional radiology (IR).

KEY ISSUES

- The scope of work of radiologists has expanded to include other procedures, including ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and IR.

- Due to the costly and immovable equipment and, usually, the limited number of radiologists, the service is usually provided in one center, which facilitates acquisition of health care associated infections.

- Usually, there is a shortage of knowledge and skills concerning issues of asepsis and antisepsis among radiology department (RD) workers.1

- Support staffs and technologists, particularly those working outside the RD, are not usually the target of IPC interventions

- With globalization, there is greater hazard of exposure to infectious diseases such as coronavirus, mainly if infected patients are not diagnosed on time. It is to be emphasized that during incubation period coronavirus could be transmitted as well

- Radiology rooms are used for both inpatients and outpatients, which often leads to contamination of surfaces, apparatuses, and equipment.

- Portable radiology units usually are contaminated and represent vehicles of microorganisms’ transmission.

- Adhesive tape (markers), 2 and lead aprons can be colonized, and serve as reservoirs for infection.3

- Filmcards used in radiation therapy become contaminated through direct and indirect contact and are a potential source of cross-infection.

- CT area. The automatic injectors,5 used for intravenous (IV) fluid administration of the contrast agent and saline flush for Multidetector CT (MDCT) have been highlighted as a potential IPC risk. Staffs are urged to perform contrast-enhanced CT more rapidly and to reduce intervals between scans to increase the throughput of patients. Syringes and other disposables are usually shared between patients to minimize set up time, thus creating contamination hazards. It is worth mentioning that catheter related blood stream infections (CRBSI) are highly associated with this kind of interventions with IV fluids (refer to ISID’s Guide to Infection Control in the Healthcare Setting; Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infections- Bundles in Infection Prevention and Safety).

- Magnetic resonance imaging. The machine bore is the most common source of infection mainly because it is difficult to access and is usually overlooked during routine decontamination.1

- Waiting areas. Prolonged exposure of patients and accompanying family members, especially in a suboptimal ventilated setting, raises an inevitable possibility of infection transmission, particularly in the context of the outbreaks of highly contagious diseases like COVID 19.6

- Ready rooms. The surfaces and devices used in these rooms can serve as source of pathogenic organisms, e. g., illuminated venipuncture assist device (Vein finder).7

- Workstations used by physicians and technologists to capture, edit, and save images can be contaminated with even higher levels of microbial organisms than adjacent toilet seats and doorknobs.8

-

Ultrasonography. Diagnostic medical sonography is a multi- specialty profession comprised of abdominal sonography, breast sonography, cardiac sonography, obstetrics/gynecology sonography, pediatric sonography, phlebology sonography, vascular technology/ sonography, and other emerging clinical areas. Common US procedures and transducer/ probe types are classified into non- critical, semi-critical and critical: 9

- Non- critical; used on healthy skin

- Semi-critical; endocavitary procedures (vagina, rectum, esophagus) contact with mucous membranes or non-intact skin or a device that contacts mucous membranes or non-intact skin

- Critical; intraoperative, examinations of immunocompromized and all ages of critically- ill patients.

- Interventional radiology. Interventional radiologists perform various imaging-guided minimally invasive procedures. These procedures may pose IPC concerns applicable to many other procedures performed outside the radiology unit.10

KNOWN FACTS

- An Italian study reported that 41.7% of X- ray tubes and 91.7% of control panels and imaging plates in the RD imaging rooms were contaminated.11,12 X-ray machines mostly carry Gram-negative organisms, especially Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosaand Acinetobacter baumannii.13 These organisms can strongly adhere to devices' plastic and metal components and can survive for more than two weeks.14 Poor environmental control leads to accumulation of soil which are easily contaminated with Bacillus species.15 In one study, MRI machines were found to be more prone to MRSA colonization.16

- Survival rate of bacteria is high on adhesive tapes (markers).2 Lead aprons become contaminated mainly in the front because they are regularly engulfed in exudate, blood, bodily discharge, and surgical debris/residue.3 Bacilli, diphtheroids and fungal spores are usually found on almost 92% of radiological markers and on lead aprons.2

- Suboptimal decontamination protocols in the RD have been documented in many reports.8,13

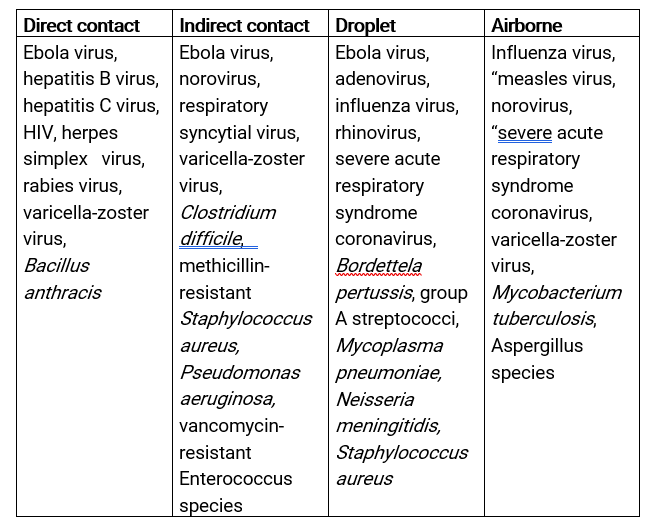

Table 1. Microorganisms that can be transmitted by radiology procedures. This list is not in-depth, and many organisms may be transmitted through several routes.17

- If successfully trained, RD healthcare workers (HCWs) have the ability to break the chain of infections.15

Ultrasound

- Recent studies have documented the prevalence of bacterial contamination on ultrasound probes, cords and keyboards. Once any surface is colonized, pathogens can survive for very long periods. Post-contamination survival will be even longer with coexistent organic material.19

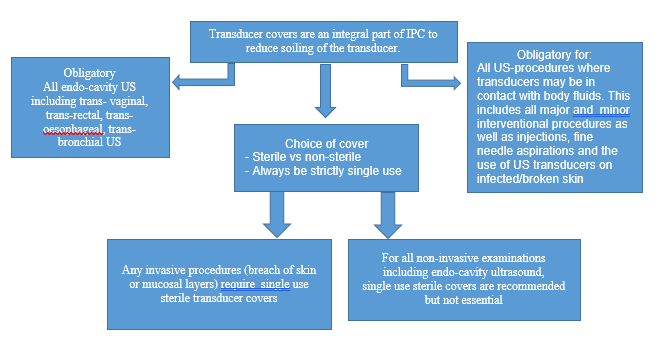

- Transducer covers are not generally used. If used, the Spaulding Classification should not be altered since they may have micro-perforations and they can tear.20

- US gel can become contaminated due to poor quality and faulty use and storage. Gel heating encourages microorganisms’ growth. Recently, contaminated US gel has been reported as one of the most common sources for outbreaks caused by Burkholderia cepacia.21-25 It may also be tainted with other organisms of importance to HAI.26-30

- Failure to follow sound IPC practices with contaminated transducers, or covers have been associated with infection outbreaks. Pseudomonas aeruginosa,31,32 and other microorganisms may be incriminated.33,34 transmission of HCV by ultrasonic procedures has been reported.35Although rare, it could be of importance in countries where HCV in endemic like Egypt, Georgia and others.36Computed tomography

- Frequent handling of automatic injectors while the system is assembled and refilled increases the risk of contamination of tubes and syringes. Even single or multiple uses of syringes/injection systems under routine clinical conditions constitute infection hazards.5 It is worth mentioning that the syringes, disposable tubes, and connectors of CT injectors are approved for a single use only as stated by Regulatory Authorities.37

- Warming of contrast and saline syringes to 37°C by the injector to reduce viscosity and facilitate administration provides optimal conditions for organism reproduction.

- Iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast agents can be contaminated due to improper storage and multiple dosages from the same vial.38Interventional radiology

- To guide the required level of decontamination, vascular intervention procedures are categorized as clean and clean-contaminated, whereas nonvascular interventions are categorized as clean, clean-contaminated and dirty.

- Insertion site infection after an interventional procedure is one of the major causes of HCAIs in IR. In the NICU, the incidence of such infections is 4.3/100 interventional procedures.39

SUGGESTED PRACTICE

Waiting Area

1. Regular and frequent environmental cleaning; at least thrice a day at fixed times and whenever required. Terminal disinfection is done using household bleach containing 5000 ppm available chlorine. Remove spillage of blood/organic materials first by solution containing 10.000 ppm available chlorine.40

2. Adequate ventilation. Air should move to the inside related to adjacent area, minimum air changes of outdoor air per hour is 2, minimum total air change per hour is 12 and all air is to be exhausted directly to outdoors.41

3. Reduce the patient’s stay in the waiting area as much as possible.

Sterilization and disinfection of RD equipment

- Strict adherence to hand hygiene procedures refer to ISID’s Guide to Infection Control in the Healthcare Setting; Hand Hygiene)

- Clean X- ray equipment, cassettes, and all other equipment with alcohol wipes and or chlorhexidine- based disinfectant between examinations.1

- Cover surfaces coming into direct contact with patients, with a disposable sheet [MRI Non-Magnetic Poly Vinyl Chloride (PVC)] that is changed between patients.

- Use wipes and alcohol gel (70% alcohol) for decontamination of radiographic markers.1 Specific attention is required for ribbon markers; the most difficult to decontaminate.42

- Disinfect MRI machine by 500–2000 mg/L chlorine-containing disinfectant.43 If it is not resistant to corrosion, wipe and disinfect with 2% double-chain quaternary ammonium salt or 75% ethanol twice or more daily. Use a disposable disinfectant wipe for cleaning and disinfection of one complete step. Disinfect at any time when there are visible pollutants, the disposable wipe shall be used first to remove the pollutants, followed by routine disinfection. Pay attention to disinfection time, most products need to be allowed to sit for 5-10 minutes. Due to difficult access to pores, it is recommended to spray the disinfectant thoroughly into them.44

- Use radiation therapy filmcards for a single patient. Properly dispose of after each use.

- Use syringe, tube, and connector of the automatic injectors for only one patient. Regular unannounced evaluations of the hygiene of the CT department are recommended.37

- Radiology Department/Service Personnel

- Adequate staff resources.45

- Provide vaccinations against preventable diseases.

- Provide adequate training in IPC.

- Develop, emphasize, monitor, and evaluate hand hygiene protocols.46

- Provide adequate supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) and educate personnel on proper use.

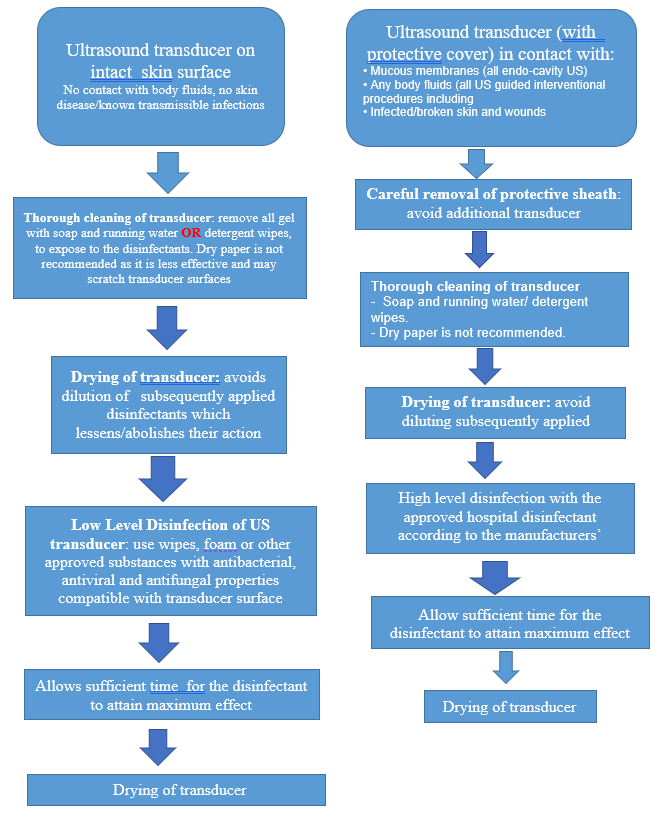

Ultrasound- The entire ultrasound unit must be considered a potential source of infection.

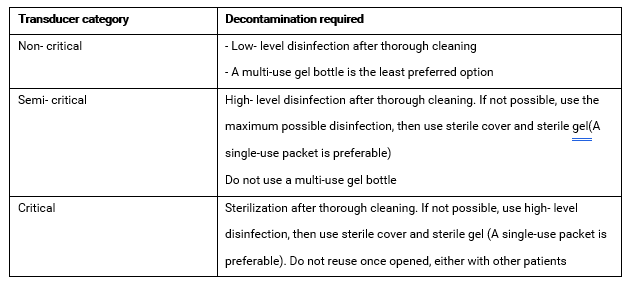

Table 2. Transducer processing according to Spaulding Classification.20

- Determine the expected Spaulding category before starting the procedure. When it is difficult to anticipate, apply the higher category.

- For safe use of ultrasound gel47

1. Ensure gel and containers are physically intact and have not exceeded the expiry date.

2. It is preferred to use a single- use gel bottle. However, it is expensive. If used discard unused portions immediately after examination of each patient.

3. If using a multi-use gel bottle,• Ensure the tip of the bottle does not come in contact with anything.

• Discard after use in an isolation precaution setting.

• Use a dispensing device for filling.

• Label the bottle with the date of refilling, discard after one week or when physically soiled. - Use dry heat to warm gel, keeping bottles upright in warmers.

- Immediately discard transducer cover if damaged during procedure, consequently Spaulding Classification may need to be altered.

Interventional radiology

- The IR suite is to be considered a ‘‘very high- risk area.48

- Use antibiotic prophylaxis appropriately.49-51

- For clean and clean-contaminated procedures an absolute sterile technique should be followed. Contaminated and dirty procedures sterile technique is preferred. At the very least a clean environment with sterile instrumentation should be available.52

- Recommendations to prevent CRBSI (refer to ISID’s Guide to Infection Control in the Healthcare Setting; Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infections- Bundles in Infection Prevention and Safety

SUGGESTED PRACTICE IN UNDER-RESOURCED SETTINGS

- To ensure the facility has the capability to adequately clean and reprocess the US transducers. The manufacturer’s Instructions for Use (IFU) should be reviewed before purchasing.

- Implementation of IPC policies and procedures in IR rooms is challenging. The equipment is generally used for twelve or more hours every day. Moreover, some of the devices may be on loan, or simply “borrowed” from other parts of the hospital. It is crucial to provide adequate supply of PPE and hand hygiene requirements and train personnel in following Isolation Precautions.

- Ensure the availability of hand hygiene requirements

- Provide adequate supply of PPE

- Insist on wearing masks, performing hand hygiene, and proper use of other PPE.

- Provide firm training and supervision in knowledge and skills of IPC.

- Remotely control or keep 1 m distance from patients.44

- Clean and disinfect medical equipment, contaminated articles, surfaces and floors.

- The surface of the CT equipment should be immediately decontaminated after the patient’s examination with solutions containing 5000- 10,000 ppm available chlorine.42

- Emphasize environmental ventilation of examination rooms and if possible, disinfect air by hydrogen peroxide.

- Waiting areas.

- It is suggested to create a separate entry for waiting area

- When available, the use of open areas is encouraged.

- Minimize, as much as possible, gathering of patients with other patients, and family members in closed RD waiting rooms.

- Regular environmental cleaning including the toilet e.g. twice/day with more frequent cleaning of high-touch surfaces.

- Imaging examination is important in the diagnosis of COVID 19. Radiology HCWs have a high occupational infection risk like those in ICUs and dedicated COVID wards.54

- Imaging examination is important in the diagnosis of COVID 19. Radiology HCWs have a high occupational infection risk like those in ICUs and dedicated COVID wards.54

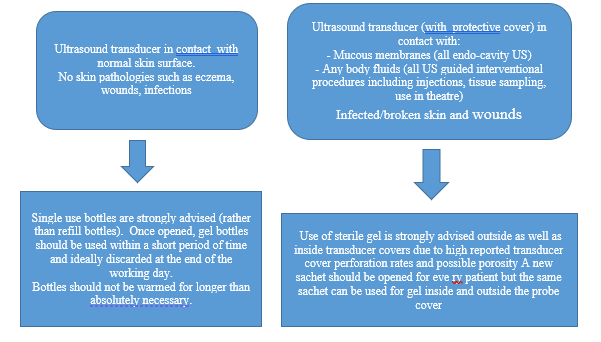

- When developing IPC guidelines, consider that diagnostic/ therapeutic services for suspected/confirmed COVID cases may be provided by existing hospitals among other services delivered, or by standing alone/isolation facilities dedicated only for COVID cases.When developing IPC guidelines, consider that diagnostic/ therapeutic services for suspected/confirmed COVID cases may be provided by existing hospitals among other services delivered, or by standing alone/isolation facilities dedicated only for COVID cases.Adequate ventilation in the waiting area. Naturally ventilated with good air flow or if air- conditioned, 6-air-change/ hour is suggested.6Adopt a modified Spaulding Classification for use and reprocessing of US probes.53 Classify into non-critical (non-invasive) if contacting intact skin only, so requiring low level disinfection, and critical (invasive). Critical probes are those coming in contact with mucous membranes, and body fluids or used for intraoperative procedures. The rationale is that US- assisted invasive procedures range from minimal invasive fine needle aspirations to endoscopic and intraoperative. When assessing the risk of infection transmission, all these procedures breach the intact skin or mucous membranes. Taking transmission of infection during acupuncture as an example, contact of the transducer with infected materials cannot be excluded during US- assisted punctures. Consequently, any US- assisted invasive procedure or any procedure potentially causing micro-trauma to the skin or mucous membranes has to be categorized as critical. The “semi-critical” category of the Spaulding Classification describing devices that are in contact with intact mucous membranes of non-sterile body sites such as the vagina needs to be omitted. That is because the integrity of these mucous membranes cannot be ensured, and possibility of micro-trauma can never be excluded. The generally accepted recommendations for disinfection are similar to those for critical procedures. This modification is important in the context of the suboptimal work environment in LMICs, figures, 1. A, B, C.

- Imaging examination is important in the diagnosis of COVID 19. Radiology HCWs have a high occupational infection risk like those in ICUs and dedicated COVID wards.54

Infection Prevention and Control in the Radiology Department/Service in the COVID 19 Era

- Imaging examination is important in the diagnosis of COVID 19. Radiology HCWs have a high occupational infection risk like those in ICUs and dedicated COVID wards.54

- When developing IPC guidelines, consider that diagnostic/ therapeutic services for suspected/confirmed COVID cases may be provided by existing hospitals among other services delivered, or by standing alone/isolation facilities dedicated only for COVID cases.

- For the first case, the followings are important:

- Formulating protocols for receiving patients from outside or from other hospital departments and transfer to RD.

- Establishing “clean” and “contaminated” zones, with dedicated transfer routes and separate CT scanners. In this context, the “contaminated” zone would refer to areas traversed by suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19. If it is logistically challenging, radiological procedures can be performed for COVID-19 confirmed/suspected cases in batches, within pre-specified timeslots. This is usually conducted at the end of the day after which the radiology space should be thoroughly cleaned.

- For both cases

- Ensure the availability of hand hygiene requirements

- Provide adequate supply of PPE

- Insist on wearing masks, performing hand hygiene, and proper use of other PPE.

- Provide firm training and supervision in knowledge and skills of IPC.

- Remotely control or keep 1 m distance from patients.44

- Clean and disinfect medical equipment, contaminated articles, surfaces and floors.

- The surface of the CT equipment should be immediately decontaminated after the patient’s examination with solutions containing 5000- 10,000 ppm available chlorine.42

- Emphasize environmental ventilation of examination rooms and if possible, disinfect air by hydrogen peroxide.

- Waiting areas.

a. It is suggested to create a separate entry for waiting area

b. When available, the use of open areas is encouraged.

c. Minimize, as much as possible, gathering of patients with other patients, and family members in closed RD waiting rooms.

d. Regular environmental cleaning including the toilet e.g. twice/day with more frequent cleaning of high-touch surfaces.

e. Adequate ventilation in the waiting area. Naturally ventilated with good air flow or if air- conditioned, 6-air-change/ hour is suggested.6

- For providing radiation therapy, optimizing facility utilization and personnel workload can help to improve appointment compliance. Active patient flow management can help Radiation Oncologists to continue and initiate treatments safely, instead of cancelling indicated therapies.55

CONTROVERSIAL ISSUES

Ultrasound

- Because of the sensitivity of the transducer’s materials and electronics to some reprocessing techniques, gaps may exist in the ability to perform the desired method of reprocessing. Therefore, users should recognize that optimum practices will evolve over time based on new research.

Interventional radiology

- Insertion site infection after an interventional procedure is one of the major causes of HCAIs in IR. Use of antibiotic is recommended but their effectiveness is still unknown.

- There is a general lack of published randomized controlled studies on the subject concerning mandatory recommendations during IR. A physician may deviate from provided guidelines, as necessitated by the individual patient and available resources. Adherence to available recommendations will not assure a successful outcome in every situation.

SUMMARY

The objectives of this chapter is to highlight the importance of IPC in activities related to the RD and to provide applicable recommendations. At the very beginning, good basic hygiene standards are crucial. All equipment, devices and instruments should be easily decontaminated and must be approved prior to use. All items coming in direct patient contact must be properly reprocessed in the way rendering it safe for the intended use. Currently, the importance of the RD has been emphasized with the emergence and spread of COVID-19. The close and frequent contact of radiographers with patients during radiological workflow have placed radiographers at a great infection risk. Key management and IPC procedure during the outbreak have been outlined.

REFERENCES

- Ilyas F, Burbridge B, Babyn P, et al. Health Care–Associated Infections and the Radiology Department. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2019;50:596-606.

- Hodges A. (2001). Radiographic Markers: Friend or Fomite? Radiol Technol. 2001;73(2):183–185.

- Contaminated X-Ray Aprons And The Risk Of HAIs. Available at: https://blog.universalmedicalinc.com/contaminated-x-ray-aprons-and-the-risk-of-hais/, accessed 30th August 2021.

- Lawlor D, Cannon K, Duan Q, Jensen, K. (2012). Filmcards Used in Radiation Therapy: Are They a Potential Source of Cross-infection? J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2012;43(1):52–59.

- Buerke B, Sonntag AK, Fischbach R, Heindel W, Tombach B. Automatic Injectors in Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Computed Tomography: Pilot Study on Hygienic Aspects. Rofo. 2004;176:1832-1836.

- Roadmap to improve and ensure good indoor ventilation in the context of COVID-19”; available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240021280. Accessed 31st August 2021.

- O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP, et al. Guidelines for the Prevention of Intravascular Catheter- Related Infections. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-10):1-29.

- Duszak R. Jr., Lanier B, Tubbs JA, et al. (2014). Bacterial Contamination of Radiologist Workstations: Results of a Pilot Study. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11(2):176–179.

- Australasian Society for Ultrasound in Medicine. Guidelines for Reprocessing Ultrasound Transducers. Australas. J. Ultrasound Med. 2017;20:30– 40.

- Taslakian B, Ingber R, Aaltonen E, Horn J, Ryan Hickey. Interventional Radiology Suite: A Primer for Trainees. J Clin Med. 2019;8(9):1347-1361.

- Ustunsoz B. (2005). Hospital Infections in Radiology Clinics. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2005;11(1):5–9.

- Giacometti M, Gualano MR, Bert F, et al. (2014). Microbiological Contamination of Radiological Equipment. Acta Radiol. 2014;55(9):1099–1103.

- Levin PD, Shatz O, Sviri S, et al. (2009). Contamination of Portable Radiograph Equipment with Resistant Bacteria in the ICU. Chest. 2009;136(2):426–432.

- Lawson SR, Sauer R, Loritsch MB. Bacterial Survival on Radiographic Cassettes. Radiol Technol. 2002;73(6):507-510.

- Waite RC, Velleman Y, Woods G, Chitty A, Freeman MC. Integration of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for the Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases: a Review of Progress and the Way Forward. Int Health. 2016;8(S1),i22-i27

- Shelly MJ, Scanlon TG, Ruddy R, et al. (2011). Meticillin- Resistant Staphylococcus aureus(MRSA) Environmental Contamination in a Radiology Department. Clin Radiol. 2011;66(9),861–864.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. National Guidelines for Infection Prevention and Control in Healthcare Facilities; available at: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/National%20Guidelines%20for%20IPC%20in%20HCF%20-%20final%281%29.pdf. Accessed 31st August 2021.

- Schmidt JM. Stopping the Chain of Infection in the Radiology Suite. Radiol Technol. 2012;84(1):31–48.

- Abdelfattah R, Al-Jumaah S, Al-Qahtani A, et al. Outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia bacteraemia in a Tertiary Care Center Due to Contaminated Ultrasound Probe Gel. J Hosp Infect. 2018;98(3):289-294.

- Rutala WA, Weber DJ, the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Guidelines for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008, update: May 2019. Page 20; available at: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/disinfection/. Accessed 3rd September 2021

- Viderman D, Khudaibergenova M, Kemaikin V, Zhumadilov A, Poddighe D. Outbreak of Catheter- Related Burkholderia cepacia Sepsis Acquired from Contaminated Ultrasonography Gel: the Importance of Strengthening Hospital Infection Control Measures in Low Resourced Settings. Infez Med. 2020;28(4):551-557.

- Solaimalai D, Devanga Ragupathi N, Ranjini K, et al. Ultrasound Gel as a Source of Hospital Outbreaks: Indian Experience and Literature Review. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2019;37(2):263-267.

- Shaban RZ, Maloney S, Gerrard J, et al. Outbreak of Health Care- Associated Burkholderia cenocepacia Bacteremia and Infection Attributed to Contaminated Sterile Gel Used for Central Line Insertion under Ultrasound Guidance and other Procedures. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(9):954-958.

- Multistate Outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia Infections Associated with Contaminated Ultrasound Gel; available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/outbreaks/b-cepacia-ultrasound-gel/index.html. Accessed 4 September 2021.

- Jacobson M, Wray R, Kovach D, et al. Sustained endemicity of Burkholderia cepacia Complex in a Pediatric Institution, Associated with Contaminated Ultrasound Gel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27:362–366.

- Yagnik KJ, Kalyatanda G, Cannella AP, Archibald LK. Outbreak of Acinetobacter baumanniiAssociated with Extrinsic Contamination of Ultrasound Gel in a Tertiary Center Burn Unit. Infect Prev Pract. 2019;1(2):100009.

- Olshtain-Pops K, Block C, Temper V, et al. An Outbreak of Achromobacter xylosoxidansAssociated with Ultrasound Gel Used during Transrectal Ultrasound Guided Prostate Biopsy. J Urol. 2011;185: 144–147.

- Oleszkowicz S, Chittick P, Russo V, et al. Infections Associated With the Use of Ultrasound Transmission Gel: Proposed Guidelines to Minimize Risk. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:1235–1237.

- Chittick P, Russo V, Sims M, et al. An Outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Respiratory Tract Infections Associated with Intrinsically Contaminated Ultrasound Transmission Gel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:850–853.

- Provenzano DA, Liebert MA, Steen B, et al. Investigation of Current Infection- Control Practices for Ultrasound Coupling Gel: a Survey, Microbiological Analysis, and Examination of Practice Patterns. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2013;38:415–424.

- Seki M, Machida H, Yamagishi Y, Yoshida H, Tomono K. Nosocomial Outbreak of Multidrug- Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Caused by Damaged Transesophageal Echocardiogram Probe Used in Cardiovascular Surgical Operations. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19(4):677-681

- Paz A, Bauer H, Potasman I. Multiresistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa associated with contaminated transrectal ultrasound. J Hosp Infect. 2001;49(2):148-149.

- Koibuchi H, Kotani K, Taniguchi N. Ultrasound Probes as a Possible Vector of Bacterial Transmission. Med Ultrason. 2013;15(1):41-4

- Keys M, Sim B, Thom O, et al. Efforts to Attenuate the Spread of Infection (EASI): a Prospective, Observational Multicentre Survey of Ultrasound Equipment in Australian Emergency Departments and Intensive Care Units. Crit Care Resusc. 2015;17:43–46.

- Ferhi K, Roupret M, Mozer P, et al. Hepatitis C Transmission after Prostate Biopsy. Case Rep Urol. 2013;2013:797248.

- Amer FA. Large- Scale Hepatitis C Combating Campaigns in Egypt and Georgia; Past, Current and Future Challenges. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2018;12:404-414.

- Buerke B, Mellmann A, Stehling C, et al. Microbiologic Contamination of Automatic Injectors at MDCT: Experimental and Clinical Investigations. AJR. 2008;191:W283–W287.

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, et al. Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health- Care Settings– 2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52:1-61

- Clements KE, Fisher M, Quaye K, et al. (2016). Surgical Site Infections in the NICU. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:1405–1408.

- Amer F. Decontamination. In: Hospital Infection Control, Part I. (3rd Edition). LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, Maude Avenue, Sunnyvale, CA 94085, USA: 2017; 56-57.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities (2003) Appendix B. Air; available at: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/environmental/appendix/air.html#tableb2. Accessed 25 September 2021.

- Tugwell J, Maddison A. Radiographic Markers – A Reservoir for Bacteria? Radiography. 2011;17(2):115–120.

- Public Health Ontario. Chlorine Dilution Calculator; available at: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/health-topics/environmental-occupational-health/water-quality/chlorine-dilution-calculator. Accessed 5 September 2021

- Long X, Zhang L, Alwalid O, et al. Radiology Department Preventive and Control Measures and Work Plan During COVID-19 Epidemic- Experience from Wuhan. Chin J Acad Radiol. 2021;4:1–8.

- Huttunen R, Syrjanen J. Healthcare Workers as Vectors of Infectious Diseases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33(9):1477–1488.

- Aso M, Kato K, Yasuda M, et al. Hand Hygiene During Mobile X- Ray Imaging in the Emergency Room. Nihon Hoshasen Gijutsu Gakkai Zasshi. 2014;67(7):793–799.

- Public Health England. Good Infection Prevention Practice: Using Ultrasound Gel; available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ultrasound-gel-good-infection-prevention-practice. Accessed: 7 September 2021.

- Huang SY, Philip A, Richter M D, et al. (2015). Prevention and Management of Infectious Complications of Percutaneous Interventions. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2015;32(2):78–88.

- Sutcliffe JA, Briggs JH, Little MW, et al. Antibiotics in interventional radiology. Clin Radiol. 2015;70(3):223–234.

- Khan W, Sullivan KL, McCann JW, et al. Moxifloxacin Prophylaxis for Chemoembolization or Embolization in Patients with Previous Biliary Interventions: a Pilot Study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197(2):W343–W345.

- Venkatesan AM, Kundu S, Sacks D, et al. Practice Guidelines for Adult Antibiotic Prophylaxis during Vascular and Interventional Radiology Procedures. Written by the Standards of Practice Committee for the Society of Interventional Radiology and Endorsed by the Cardiovascular Interventional Radiological Society of Europe and Canadian Interventional Radiology Association. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29(11):1483-1501

- Chan D, Downing D, Keough CE, et al. Joint Practice Guideline for Sterile Technique during Vascular and Interventional Radiology Procedures: From the Society of Interventional Radiology, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, and Association for Radiologic and Imaging Nursing, for the Society of Interventional Radiology (Wael Saad, MD, Chair), Standards of Practice Committee, and Endorsed by the Cardiovascular Interventional Radiological Society of Europe and the Canadian Interventional Radiology Association. Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012; 23:1603–1612.

- Nyhsen CM, Humphreys H, Koerner RJ, et al. Infection Prevention and Control in Ultrasound – Best Practice Recommendations from the European Society of Radiology Ultrasound Working Group. Insights Imaging. 2017;8:523–535

- Finkenzeller T, Lenhart S, Reinwald M, et al. Risk to Radiology Staff for Occupational COVID-19 Infection in a High-Risk and a Low-Risk Region in Germany: Lessons from the "First Wave". Rofo. 2021;193(5):537-543.

- Akuamoa-Boateng D, Wegen S, Ferdinandus J, et al. Managing Patient Flows in Radiation Oncology during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Reworking Existing Treatment Designs to Prevent infections at a German Hot Spot Area University Hospital. Onkol S. 2020;196(12):1080–1085 .