GUIDE TO INFECTION CONTROL IN THE HEALTHCARE SETTING

HORIZONTAL VS VERTICAL INFECTION CONTROL STRATEGIES

Authors: Salma Abbas, MBBS, Michael Stevens, MD, MPH

Chapter Editor: Shaheen Mehtar, MBBS. FRC Path, FCPath, MDP

Print PDF

KEY ISSUE

- Healthcare-associated infections such as central line-associated bloodstream infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, ventilator-associated pneumonias, and surgical site infections represent a major challenge for healthcare today1. These infections are often caused by multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin resistant Enterococci (VRE), and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE)1. Infection control strategies designed to prevent the spread of these infections can be grouped into two categories: vertical and horizontal. Vertical strategies focus on a single organism while horizontal strategies aim to control the spread of multiple organisms simultaneously2.

KNOWN FACTS

- Active surveillance and testing (AST) is a vertical infection prevention strategy. Patients colonized with organisms such as MRSA, VRE, and CRE are identified by culturing (or using other diagnostic testing) at various anatomic sites such as the nares, axillae, and rectum. This may be followed by cohorting or isolating patients and the use of additional measures such as decolonization2.

- Horizontal strategies include hand hygiene, universal decolonization, selective digestive tract decolonization, antimicrobial stewardship, and environmental cleaning2.

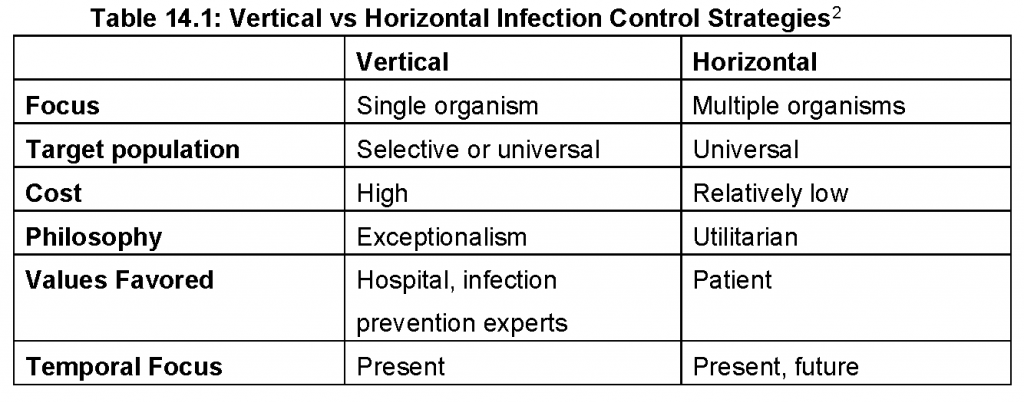

- Vertical strategies are costly and their impact is short-lived. Horizontal strategies are utilitarian and cost-effective. Table 14.1 summarizes the key features of vertical and horizontal strategies2.

CONTROVERSIAL ISSUES

- Though still in use, vertical strategies such as AST remain controversial (outside of outbreak settings)3,4. A comparative effectiveness review of universal MRSA screening revealed a low strength of evidence associating universal screening with reductions in healthcare-associated MRSA infection; this same review did not reveal other screening strategies to be effective5.

- Universal decolonization is a popular horizontal infection prevention strategy. Chlorhexidine (CHG), the agent of choice, for patient bathing is generally well-tolerated and active against Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and fungal pathogens. Its widespread use raises concerns over the development of resistance, however. Genes implicated in CHG resistance include qac A/Bamong MRSA and qac Eamong Klebsiella Although resistance is a concern, at this point in time it is believed to be a rare phenomenon6. Of note, CHG resistance testing is not routinely performed and breakpoints have not been established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)7.

- Selective digestive tract decolonization (SDD) is a prophylactic strategy designed to reduce the gastrointestinal burden of Candida species, aureus, and Gram-negative organisms. Protocols vary and may combine intravenously administered antibiotics such as third and fourth generation cephalosporins with oral polymyxin E, amphotericin B, and vancomycin. Oral and rectal surveillance cultures are then performed at regular intervals to determine the effectiveness of SDD. While effective at reducing the gastrointestinal carriage of organisms, this strategy remains controversial due to concerns for the selection of multidrug-resistant organisms8

SUGGESTED PRACTICE

Horizontal and vertical infection control strategies have their pros and cons. While horizontal strategies are generally favored, vertical interventions are useful in certain situations. The choice of infection control strategies should be informed by local epidemiology.

Active surveillance and testing (AST)

- In most non-outbreak settings, the costs associated with AST outweigh their benefits. This includes direct costs as well as opportunity costs (in terms of personnel and financial resources).

- In outbreak settings AST can be useful in controlling the spread of organisms such as MRSA and CRE9,10.

Hand Hygiene

- Hand hygiene is the most important of infection prevention strategies. This involves minimizing the spread of microorganisms between patients via the contaminated hands of healthcare workers. Hand hygiene may be implemented in conjunction with other strategies as part of a bundle11.

- The World Health Organization recommends five moments of hand hygiene: before contact with patients, before performing aseptic procedures, after exposure to body fluids, following contact with patients and contact with patient surroundings (Figure 14.1)12.

Universal Decolonization

- CHG is the most commonly used agent for decolonization. CHG bathing may be limited to high acuity areas such as ICUs or implemented hospital-wide.

- Hospitals should formulate guidelines and bathing protocols and these should be made available to hospital staff. Compliance with CHG bathing should be monitored periodically. CHG resistance should be considered but testing is not routinely recommended7.

Antibiotic Stewardship

- According to a CDC estimate, 30-50% of antibiotics prescribed in the United States are unnecessary. Antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) can help reduce antibiotic exposure, lower rates of Clostridium difficile infections and minimize healthcare costs13. Most antimicrobial stewardship activities effect multiple organisms simultaneously and have as a primary goal the prevention of the emergence of antibiotic resistance. Thus, ASPs can largely be viewed in the context of horizontal infection prevention. Additionally, ASPs can contribute to the prevention of surgical site infections via the optimized use of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis.

Environmental Cleaning

- Surfaces of bedrails, nurse call buttons, television remote controls, and medical equipment may harbor organisms such as MRSA, VRE, difficile, Acinetobacter species, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and norovirus, amongst others10.

- Staff who perform environmental cleaning should be dedicated to specific units to reduce the risk for cross-contamination. Thorough cleaning of commonly contaminated surfaces such as bedrails, bedside charts, medical equipment, and door knobs is recommended10.

- Units should be frequently monitored to ensure compliance with environmental cleaning practices.

SUGGESTED PRACTICE IN UNDER-RESOURCED SETTINGS

Infection control strategies in under-resourced areas are often limited by access to human, technologic, and financial resources. Many under-resourced areas lack infection prevention infrastructure and guidelines on optimized infection prevention practices are often not available to hospital staff members. As a result, infection surveillance is often not performed consistently, perioperative prophylactic antibiotics are often not optimally administered, and hand hygiene is suboptimal, as well14.

- Infection control programs should be created and guidelines formulated. Guidelines should be made available to hospital staff members to help ensure consistency in practices.

- Educational programs should be designed to familiarize hospital staff with infection prevention guidelines.

- Infection prevention programs should collaborate with microbiology labs to find economical means for performing surveillance and other related tests.

- ASPs should be established to promote the judicious use of antibiotics.

- Adherence to measures such as hand hygiene, perioperative antibiotic administration, and the disinfection of equipment and patient care areas should be promoted. Local epidemiology and antibiograms should inform practices at individual centers.

- Periodic assessments should be informed to ensure compliance with guidelines.

SUMMARY

Infection control strategies designed to prevent the spread of healthcare-associated infections can be grouped into two categories: vertical and horizontal. Vertical strategies focus on a single organism while horizontal strategies aim to control the spread of multiple organisms simultaneously. Horizontal strategies include hand hygiene, universal decolonization, selective digestive tract decolonization, antimicrobial stewardship, and environmental cleaning. Horizontal and vertical infection prevention strategies have their pros and cons. While horizontal strategies are generally favored, vertical interventions are useful in certain situations. The choice of infection control strategies should be informed by local epidemiology.

REFERENCES

- Scott DR. The Direct Medical Costs of Healthcare-Associated Infections in Us Hospitals and the Benefits of Prevention. 2009; available at http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/hai/Scott_CostPaper.pdf.

- Edmond MB, Wenzel RP. Screening Inpatients for MRSA — Case Closed. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368(24):2314–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1304831.

- Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Infection Control: The Case for Horizontal Rather Than Vertical Interventional Programs. Int J Infect Dis. 2010; 14(suppl 4):S3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.05.002.

- Wenzel RP, Bearman G, Edmond MB. Screening for MRSA: A Flawed Hospital Infection Control Intervention. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008; 29(11):1012–8. doi: 10.1086/593120.

- Glick SB, Samson DJ, Huang ES, et al. Screening for Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: A Comparative Effectiveness Review. Am J Infect Control. 2014; 42(2):148–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.07.020.

- Kampf G. Acquired Resistance to Chlorhexidine — Is It Time to Establish an ‘Antiseptic Stewardship’ Initiative? J Hosp Infect. 2016; 94(3):213–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.08.018.

- Abbas S, Sastry S. Chlorhexidine: Patient Bathing and Infection Prevention. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2016; 18(8):25. doi: 10.1007/s11908-016-0532-y.

- Silvestri L, van Saene HKF. Selective Decontamination of the Digestive Tract: An Update of the Evidence. HSR Proc Intensive Care Cardiovasc Anesth. 2012; 4(1): 21–9.

- Facility Guidance for Control of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). 2015; available at http://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/cre/CRE-guidance-508.pdf.

- Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDRO) Management. 2017; available at http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/MDRO/MDROGuideline2006.pdf.

- Education Courses for Healthcare Providers on Hand Hygiene: Hand Hygiene, Glove Use, and Preventing Transmission of C. difficile (2017) — WD2703 and Hand Hygiene & Other Standard Precautions to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections. 2005; available at http://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/training.html.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care; available at http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/background/5moments/en/.

- Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs. 2017; available at http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/implementation/core-elements.html.

- Weinshel K, Dramowski A, Hajdu Á, et al. Gap Analysis of Infection Control Practices in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015; 36(10):1208–14. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.160

- Gidengil CA, Gay C, Huang SS, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Strategies to Prevent Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Transmission and Infection in an Intensive Care Unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015; 36(1):17–27. doi: 10.1017/ice.2014.12.